Self-Actualization

An Avatar.Global Resource

Self-Actualization

Self-actualization is the psychological and emotional process of Healing the Physical Unit and Aligning the Bodily Ego so the Spiritual Ego might properly express.[1] This psychological term is syncretic with the LP concept of Alignment.

Syncretic Terms

Alignment > Asha, Brahmacharya, Conversion Experience, Divine Perfection, Ethical Perfection, Eudaimonia, Gonennoncwal, Heavenly Marriage, Holiness, Ka'nikonhrÌ:io, Ondinoc, Perfect Connection, Purification, Purity, Rectitude, Renunciation, Repentence, Righteousness, Samyaktva, Sane Living, Self-Actualization, Tahdhīb al-akhlāq, Taubah

Notes

In LP terms, self-actualization is the process of integration of Healing and Aligning the Bodily Ego so it may connect, and Integrate with Spiritual Ego. Connection Practice is an important component of alignment and integration.

The term "self-actualization" was coined by Abraham Maslow to refer to a dynamic process, active throughout life" and not a final end state.[2] Maslow also considered Self-Actualization to be a need

"Self-actualization is 'intrinsic growth of what is already in the organism, or more accurately of what is the organism itself.[3].

Daniels notes that there is a considerable amount of terminological inconsistency in Maslow's theorization. Maslow, he argues, "never achieved a final coherent theory of self-actualization.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag </ref>

In Maslow's words, self-actualization is "...the desire for self-fulfillment, namely, to the tendency for him [sic] to become actualized in what he is potentially. This tendency might be phrased as the desire to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming." [4]. As Maslow notes, the specific form of the needs varies from individual to individual. For some self-actualization entails working towards being the ideal mother, in others it is to be a perfection musician, and so on."

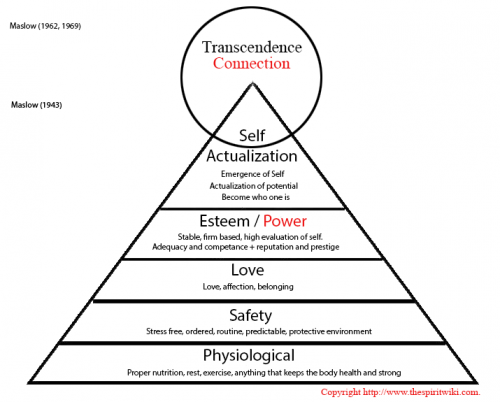

Self-actualization is the fifth of a set of Needs specified by Abraham Maslow in his Hierarchy of Needs.[5]

Two jkinds of self-actualizing people

"I have recently found it more and more useful to differentiate between two kinds (or better, degrees) of self-actualizing (SA) people, those who were clearly healthy, but with little or no experiences of transcendence, and those in whom transcendent experiencing was important and even central. As examples of the former kind of health, I may cite Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt, and probably, Truman and Eisenhower. As examples of the latter, I can use Aldous Huxley, and probably Schweitzer, Buber, and Einstein."[6]

There are elements of Ascension in Maslow's definition. "Maslow was always committed to the view that self-actualization is the actualization of the 'self'"[7] Note Maslow's secular view: "the self was always defined in a particular way - as a largely biological, but partly self-constructed,real self."[8] "self-actualization was always viewed in terms of the actualization of the individual's biological core."[9]

"The self-actualizing people I talk about are very healthy people, psychiatrically and psychologically healthy people. They could be called a superior segment of the population. Thus I, and others, have been studying not the whole human species, in an ordinary statistical sense'), not the average of the species, but a select sample, i.e., the most creative or most talented or perhaps most intelligent that we could find." [10]

"BY definition, self-actualizing people are gratified in all their basic needs (of belongingness, affection, respect, and self-esteem). This is to say that they have a feeling of belongingness and rootedness, they are satisfied in their love needs, have friends and feel loved and loveworthy, they have status and place in life and respect from other people, and they have a reasonable feeling of worth and self-respect. If we phrase this negatively - in terms of the frustration of these basic needs and in terms of pathology - then this is to say that selfactualizing people do not (for any length of time) feel anxiety-ridden, insecure, unsafe, do not feel alone, ostracized, rootless, or isolated, do not feel unlovable, rejected, or unwanted, do not feel despised and looked down upon, and do not feel deeply unworthy, nor do they have crippling feelings of inferiority or worthlessness (Maslow, 1967, p. 93).

when basic needs met, move beyond self-actualization to metamotivation, meta needs (Maslow, 1967)

It is my strong impression that the closer to self-actualizing, to fullhumanness, etc., the person is, the more likely I am to find that his &dquo;work&dquo; is metamotivated rather than basic-need-motivated. For more highly evolved persons, &dquo;the law&dquo; is apt to be more a way of seeking justice, truth, goodness, etc., rather than financial security, admiration, status, prestige, dominance, masculinity, etc. When I ask the questions: which aspects of your work do you enjoy most ? What gives you your greatest pleasures? ~1’hen do you get a kick out of your work? etc., such people are more apt to answer in terms of intrinsic values, of transpersonal, beyond-the-selfish, altruistic satisfactions, e.g., seeing justice done, doing a more perfect (Maslow, 1967, p. 102).

Characteristics

For an early summary of the characteristics of Self actualizers identified by Maslow, see http://knowthyself.nfshost.com/pages/books/maslow_self-actualization.html

"By early 1946, Maslow had thus uncovered two significant traits that seemed common to self-actualizing people: their intense desire for privacy and their tendency to experience mystical-like moments. He also had a hunch about a third trait: that emotionally healthy people see their world more accurately than their more anxiety-ridden peers." [11]ref>Maslow, Abraham. “Resistance to Acculturation.” Journal of Social Issues 7, no. 4 (November 1951): 26–29. p. 28.</ref>

Do not "fit in" with toxic culture. "They got along with the culture in various ways, but of all of them it could be said that in a certain pro- found and meaningful sense they resisted acculturation and maintained a certain inner detachment from the culture in which they were immersed."[12]

passionate about changing and improving the world. Could be revolutionary and resistance if required, but did not resist and struggle for empty reasons. "not against fighting but only against ineffective fighting." [13]

" All these people fell well within the limits of apparent conventionality in choice of clothes, of language, of food, of ways of doing things in our culture. And yet they were not really conventional, certainly not "fashionable" or "smart" or "chic." Do not act overtly unconventional, unless necessary to preserve inner sanctity. Otherwise, they go along to avoid hurting others, to maintain peace, to show respect.But able to throw off convention when going along was too annoying or expensive. [14]

"None of these people could be called authority-rebels in the adolescent or "hot" sense. They showed no active impatience or moment-to-moment, chronic, long-time discontent with the culture or preoccupation with changing it quickly, although they often enough showed bursts of indignation with injustice."[15]

"An inner feeling of detachment from the culture was not necessarily conscious but was displayed by almost all, particularly in discussions of the American culture as a whole, in various comparisons with other cultures, and in the fact that they very frequently seemed to be able to stand off from it as if they did not quite belong to it. The mixture of varying proportions of affection or approval and hostility or criticism indicated that they selected from American culture what was good in it by their lights and rejected what they thought bad in it. In a word they weighed it, assayed it, tasted it and then made their own decision."[16]

"For these and other reasons they may be called autonomous, i.e., ruled by the laws of their own character rather than by the rules of society. It is in this sense that they are not only or merely Americans, but also to a greater degree than others, members-at-large of the human species."[17]

Citation and Legal

Treat the SpiritWiki as an open-access online monograph or structured textbook. You may freely use information in the SpiritWiki; however, attribution, citation, and/or direct linking are ethically required.

Footnotes

- ↑ Daniels, M. “The Development of the Concept of Self-Actualization in the Writings of Abraham Maslow.” Current Psychological Perspectives 2 (1982): 71.

- ↑ Maslow quoted in Daniels, M. “The Development of the Concept of Self-Actualization in the Writings of Abraham Maslow.” Current Psychological Perspectives 2 (1982): 66.

- ↑ Maslow. “The Expressive Component of Behavior.” Psychological Review 56, no. 5 (September 1949): 264. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0053630.

- ↑ Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 382.

- ↑ Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

- ↑ Maslow, Abraham. “Theory Z.” Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 1, no. 2 (1969): 31–47. p. 31.

- ↑ Daniels, M. “The Development of the Concept of Self-Actualization in the Writings of Abraham Maslow.” Current Psychological Perspectives 2 (1982): 71.

- ↑ Daniels, M. “The Development of the Concept of Self-Actualization in the Writings of Abraham Maslow.” Current Psychological Perspectives 2 (1982): 71.

- ↑ Daniels, M. “The Development of the Concept of Self-Actualization in the Writings of Abraham Maslow.” Current Psychological Perspectives 2 (1982): 71.

- ↑ Maslow, A. H. (1969). The farther reaches of human nature. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1(1), 5.

- ↑ Edward Hoffman, The Right to Be Human: A Biography of Abraham Maslow (New York: McGraw Hill, 1999), 4395.

- ↑ Maslow, Abraham. “Resistance to Acculturation.” Journal of Social Issues 7, no. 4 (November 1951): 26–29. p. 26.

- ↑ Maslow, Abraham. “Resistance to Acculturation.” Journal of Social Issues 7, no. 4 (November 1951): 26–29. p. 28.

- ↑ Maslow, Abraham. “Resistance to Acculturation.” Journal of Social Issues 7, no. 4 (November 1951): 26–29. p. 26.

- ↑ Maslow, Abraham. “Resistance to Acculturation.” Journal of Social Issues 7, no. 4 (November 1951): 26–29. p. 26.

- ↑ Maslow, Abraham. “Resistance to Acculturation.” Journal of Social Issues 7, no. 4 (November 1951): 26–29. p. 28.

- ↑ Maslow, Abraham. “Resistance to Acculturation.” Journal of Social Issues 7, no. 4 (November 1951): 26–29. p. 29.